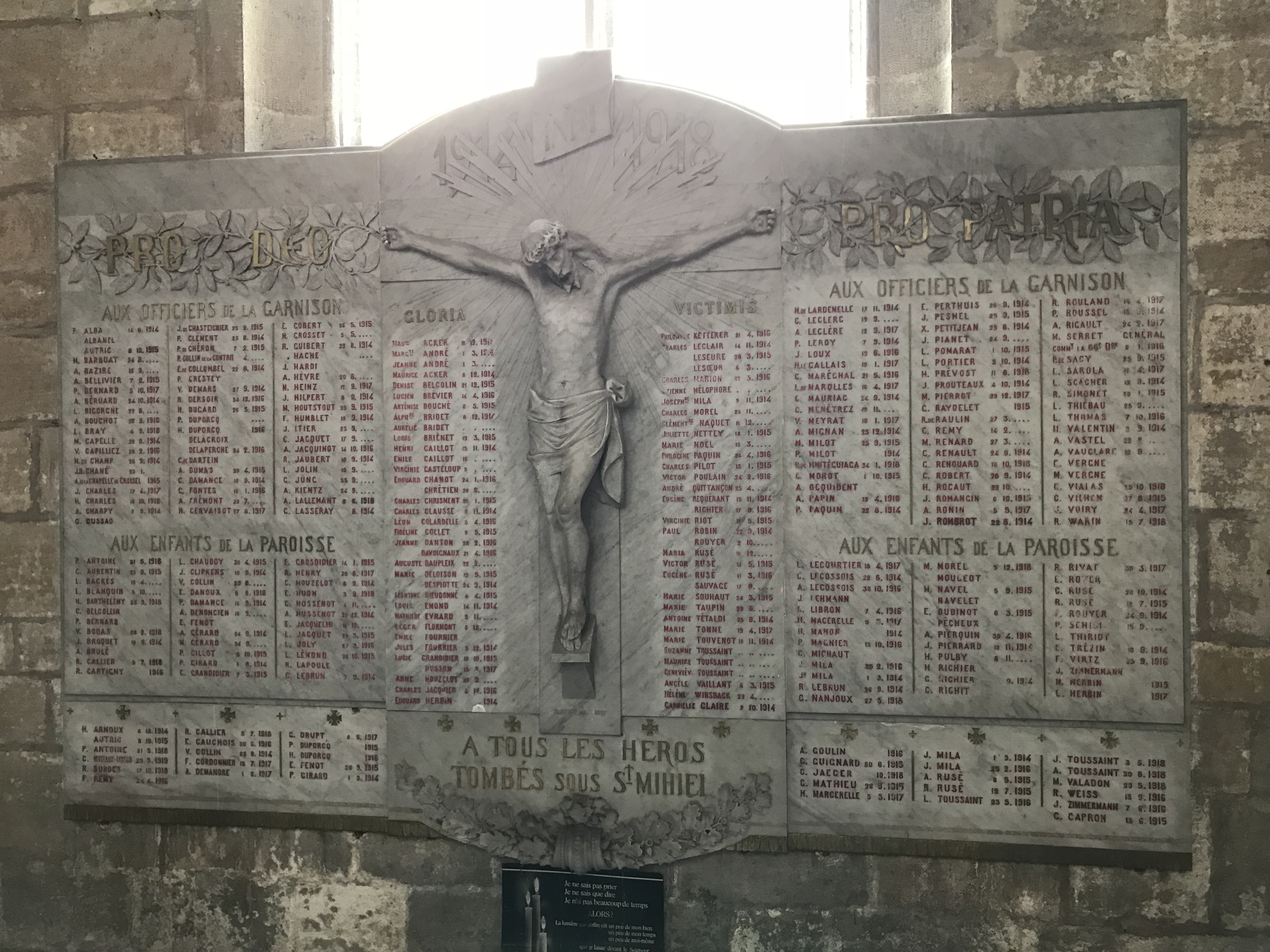

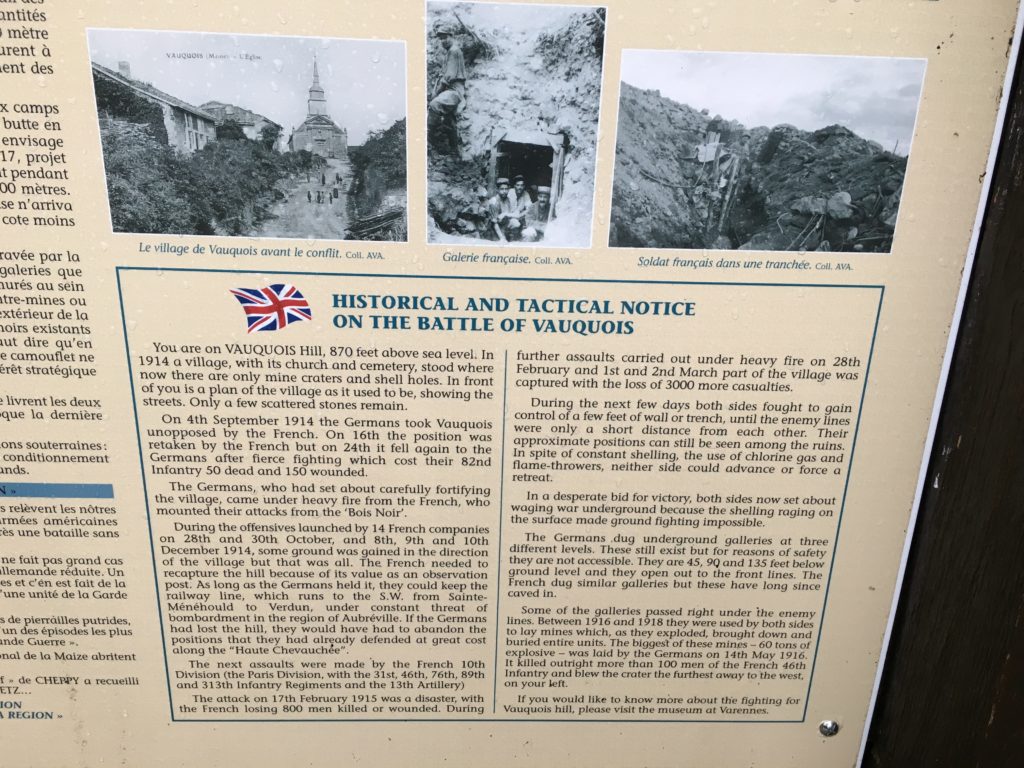

The photos in this post are from February of 2016, when my stepson Lee and I took a week to be in France for the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Verdun. On a rainy and misty weekend day, we took a tour of the Meuse-Argonne region to visit some of the more salient points of interest. One of them was the Butte de Vauquois.

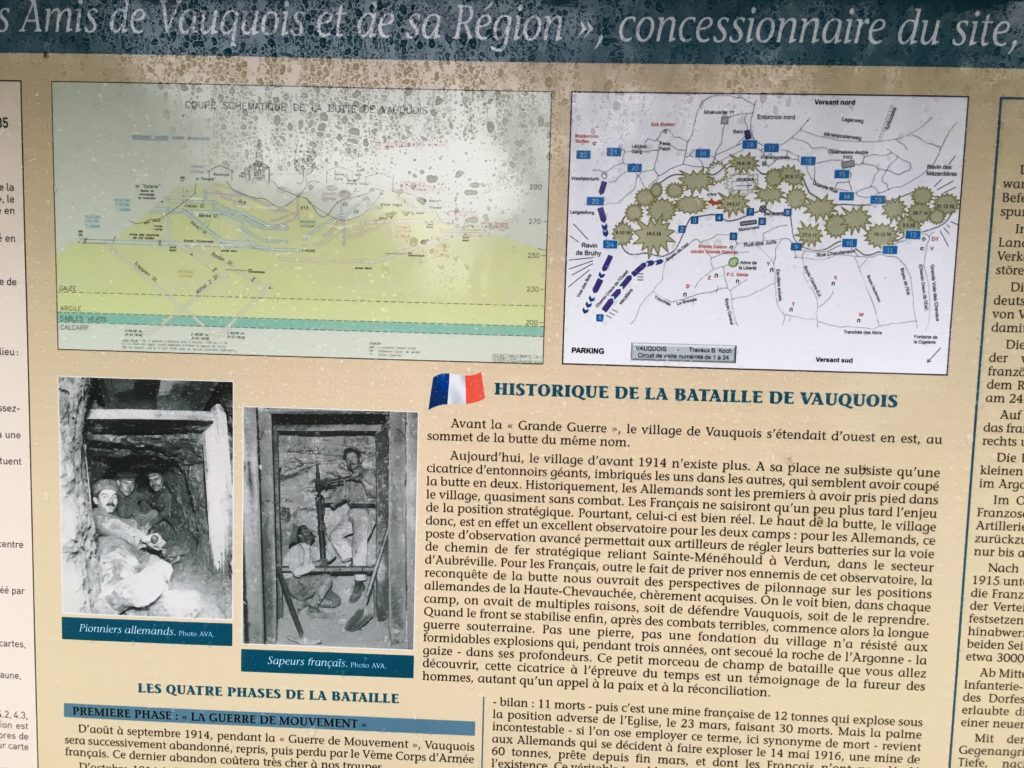

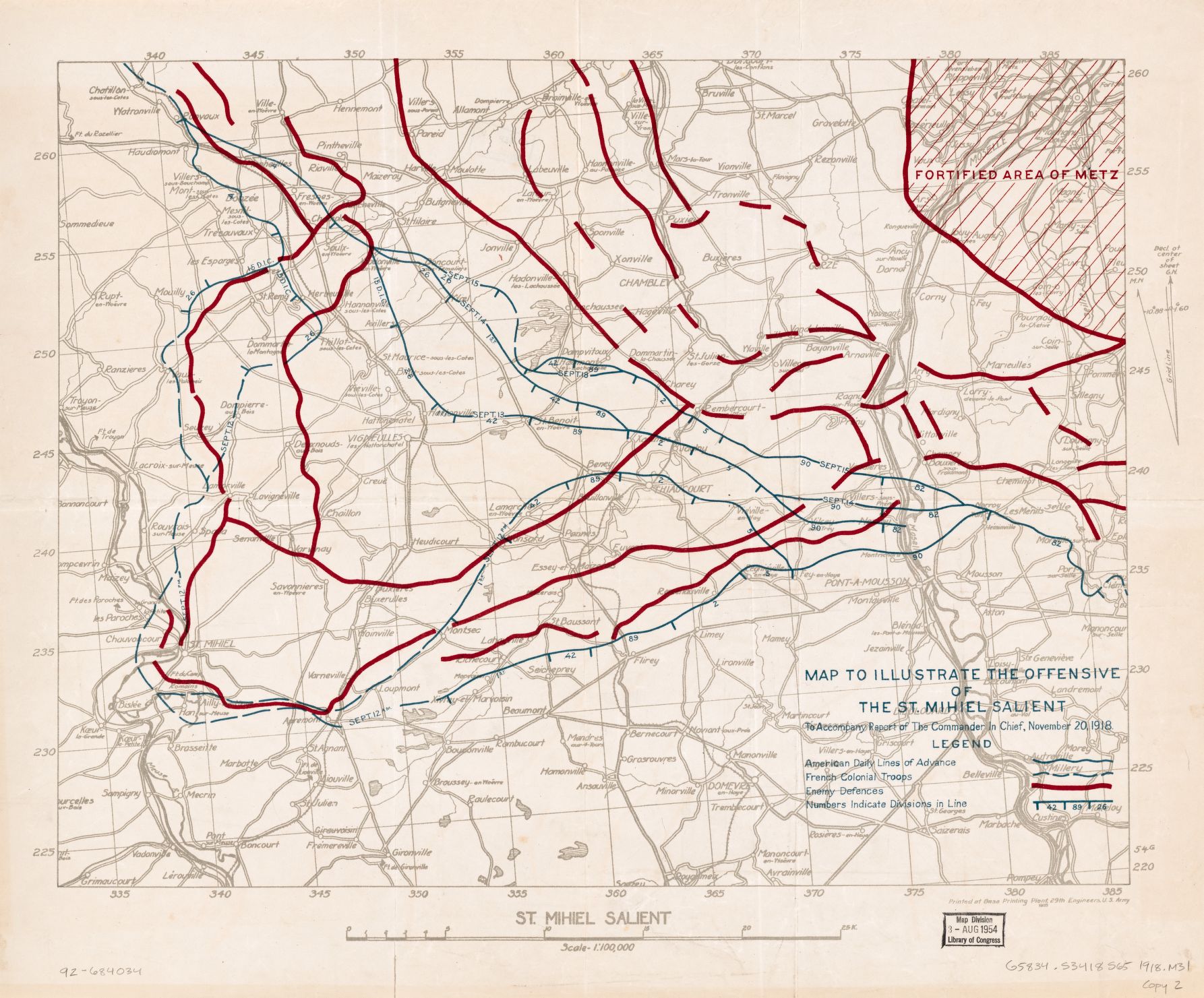

At the time I didn’t know too much about Vauquois, only that mine warfare had dominated this sector of the front and that this hill was a hinge on the Verdun salient’s western side. I had seen photos on the Web, of course, and knew the barest details of the wartime history of the hill. I knew there would be some mine craters.

When you get close you see the hill is now wooded, and even in winter this obscures the true state of the butte today. Coming up the road to the hilltop battlefield, you are coming in from the rear of the French lines. The parking lot is on the western end of the hill, and here there are numerous artifacts related to the struggle for Vauquois Hill displayed at the edges of the lot. There is a visitor center that appears to be a former dugout, and it’s a great little place full of weapons, tools, and other artifacts used in the Vauquois sector and beyond.

At the upper edge of the lot are steps that lead up to the summit of the hill, and it’s a good walk to get up there.

The first thing you will see as you clear the trees is a massive mine crater. It’s like a giant dug his hand into the hill and tore out a huge chunk of it. It’s a hole big enough to fit a house in–literally, and I mean “literally” in the real sense of the word. This is the result of the May 14, 1916 mine set off by the Germans, where 60 tons of Westfalit explosives were used in an attempt to rupture the French lines.

This isn’t the only crater like this. Get to the top of the hill–now some eighteen feet shorter due to the First World War–and you will see a chain of massive holes that bisect the Butte de Vauquois. Not only has six meters of earth and an ancient village been wiped off the top of the hill, but the heart of it has been ripped out, too.

This first time on Vauquois my brain was boggled by what my eyes were showing me. Holes of this size simply could not exist, even though I was looking at them and a short while later in them. I mean, a two-story home could fit comfortably in these craters with room to spare. To see these mine craters and know that these were man-made creations was startling.

The heart of the hill, torn open and exposed to the world.

The ground shows unmistakable evidence of the terrible events that happened here a century ago.

These mine craters are hard for the mind to comprehend.

Looking from the German lines.

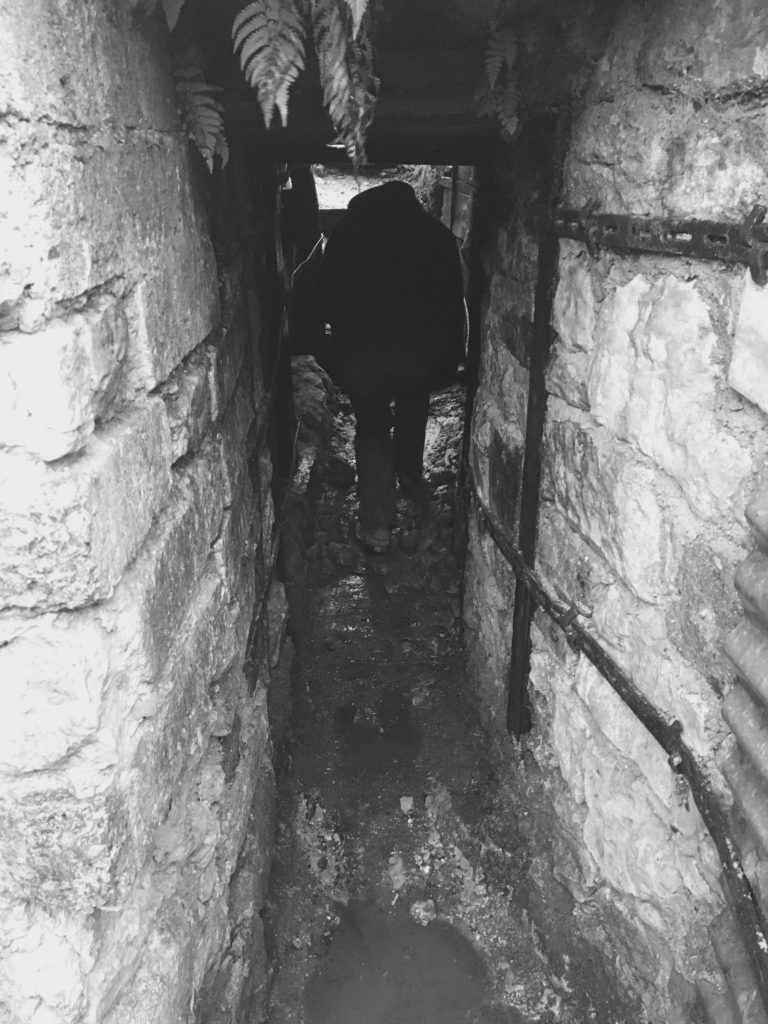

Entrance to a dugout on the Butte de Vauquois.

Yours truly.

“Know the darkness.” A future post will show what lies beneath.