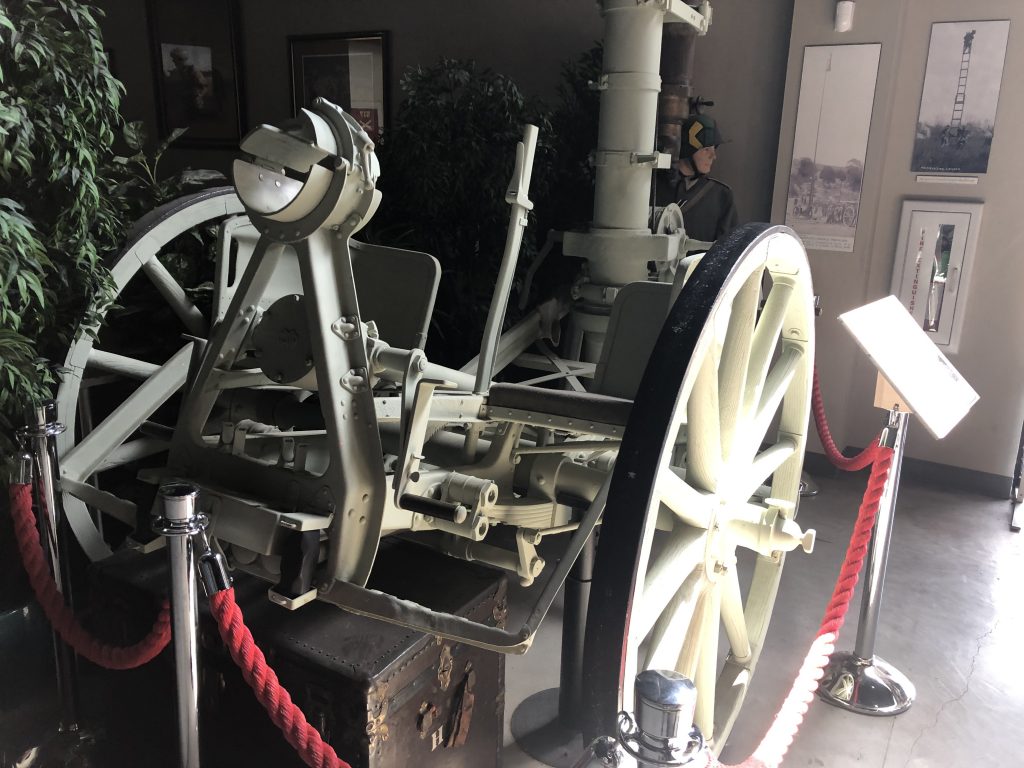

In this episode we have a very special guest: Ms. Lora Vogt, is the Curator of Education at the National World War I Museum and Memorial. Founded in 1926, the Museum holds the most comprehensive collection of Great War artifacts in the world and has been ranked one of the top 25 museums in the country. Under Ms. Vogt’s guidance, the Museum has consistently broken records for public program attendance, educational participations and developed internationally recognized curriculum and online exhibitions.

Ms. Vogt will give the BFWWP community a virtual tour of the National World War I Museum and Memorial and some of its exhibits. If you have never visited the National World War I Museum and Memorial and are on the fence about it for any reason, I am quite sure this episode will end any such doubts.

National WW1 Museum and Memorial Links:

The Panthéon de la Guerre

https://www.theworldwar.org/explore/exhibitions/past-exhibitions/panth%C3%A9on-de-la-guerre

Museum Shop:

The BFWWP is on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/BattlesoftheFirstWorldWarPodcast.

Any questions, comments or concerns please contact me through the website, www.firstworldwarpodcast.com. Follow us on Twitter at @WW1podcast, the Battles of the First World War Podcast page on FaceBook, and on Instagram at @WW1battlecast. Not into social media? Email me directly at verdunpodcast@gmail.com. Please consider reviewing the Battles of the First World War Podcast on iTunes.